Thomas Lovell Warner

Sue Warner’s Great Uncle

Thomas Lovell Warner, known as Tom, went to war in 1914 aged 20: having served on the Front Line throughout The Great War he died three years later in the military hospital at Tincourt, France. Tom was Sue Warner’s great uncle and the elder brother of Sue’s grandfather Edward Lignum Warner (known as Ted), who was married to Winifred James (The Elms), the father of Andrew Warner.

Thomas Lovell Warner, known as Tom, went to war in 1914 aged 20: having served on the Front Line throughout The Great War he died three years later in the military hospital at Tincourt, France. Tom was Sue Warner’s great uncle and the elder brother of Sue’s grandfather Edward Lignum Warner (known as Ted), who was married to Winifred James (The Elms), the father of Andrew Warner.

Tom was born on 11th January 1894 at Leicester Abbey, where the Warner family had lived since the 1700s: he was the eldest son of Charles Robert Warner and Ida Berridge. He had a sister, Rachel, born in 1891 and a younger brother, Ted, born in 1901. Charles Warner ran the family horticultural business at the Abbey: his tulip collection was renowned across the country.

Tom attended Stoneygate Preparatory School and went on to Oundle School in 1908. Tom joined the Officer Training Corps (OTC), was a school prefect, and a prominent member of the rugby XV. In July 1913 he matriculated and went up to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, to read theology. It was always Tom’s intention to enter the church after graduating but war was to interrupt his plans. Like many of his peers, Tom was a member of the Cambridge University OTC: during the war many of the university’s facilities were taken over by the OTC in support of efforts to provide its share of the huge number of young officers needed for Kitchener’s New Army. Tom left Cambridge after only one year in order to take up a commission with the 8th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, which had been formed with volunteer recruits as part of Kitchener’s Third New Army.

Tom joined the 8th Battalion in September 1914 at their basic training camp in Bourley, a tented camp about one mile from Aldershot. He did not have to undertake officer training due to acceptance of his service with the OTC at both school and university. He was joined at Bourley Camp by his cousin Isaac Lovell Berridge, who was a member of the Leicester hosiery manufacturing family, I L Berridge & Co.

Life at Bourley Camp was not easy for the men, not least because very few military supplies were available: the rapid increase in the Army’s size being unmatched by procurement of even basic khaki uniforms. The soldiers wore the emergency ‘Kitchener Blue’ – ex-Post Office blue serge uniforms – although officers like Tom were fully equipped because of their service in the OTC. However, it is clear from Tom’s letters home that he required many additional items of clothing, which he asked his sister Rachel to purchase from Adderley’s store in Leicester. A fair indication of Tom’s physical stature is his request for shirt collars size 17½. His letters home at this time also lend support to the generally accepted view of Tom as a kind, considerate and thoughtful young man: he apologises to Rachel for his shopping demands “being an awful nuisance”.

In March 1915 the 8th Battalion moved to Folkestone to join the other Leicestershire Battalions as part of the 110th (Leicestershire) Brigade; thence to Perham Down for final pre-embarkation training. On 29th July 1915, after an intense period of training, Tom joined his comrades boarding one of the troopships carrying the 110th Brigade to France. By early September 1915, Tom was in the front line trenches albeit in the beautiful countryside of the Berles au Bois sector. Relatively peaceful static warfare continued into the winter although the 8th Battalion war diary regularly reports the impact of German trench mortars and sniper fire. The biggest problem was the cold and extreme wet which reduced the morale and fitness of the men: this stretched the characters of the young officers like Tom. It is thought provoking to reflect that Tom was just 22 years old when he took command of ‘C’ Company, 8th Leicester Battalion. As an Acting Captain – a company was usually commanded by a Major or Captain – he was responsible for the well-being of about 225 men, 5 officers and 20 non-commissioned officers (NCOs).

Tom’s activities and the destiny of the 8th Battalion were inextricably entwined with the other three ‘Service’ battalions – formed in the main by volunteers – namely the 6th, 7th and 9th which made up the 110th (Leicestershire) Brigade. Wherever the brigade was moved, billeted or fought it was always with the four ‘Service’ battalions working in close cooperation and support. By July 1916 Tom’s ‘C’ Company was part of the Brigade’s efforts during the Somme Offensive: between the 14th and 16th July he fought side-by-side with over 3,000 others in the Battle of Bazentin Ridge. He was wounded during the battle, in which his commanding officer was killed – the battalion suffered 415 casualties representing nearly one half of the establishment – and Tom was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his gallant action. Only two officers remained unscathed from this intense action.

Tom was promoted to Acting Major and made 2nd in command of the Battalion in October 1916, remaining on the front line until Christmas when he spent a quiet time in reserve in the relative safety of Auchel. His rise to field rank at such a young age whilst meteoric was not necessarily that unusual as many young men had to fill the boots of those only a little older and wiser who fell in great numbers during the Somme offensive. For example, his friend Bertie Beardsley from Loughborough, with only a little more experience, had assumed command of the 8th Battalion when the colonel was killed in July 1916. Bertie was promoted to Acting Lt. Colonel and commanded the Battalion with Tom as his 2nd in command until the end of 1916.

From early January 1917 Tom kept up a regular, weekly correspondence with his younger brother Ted, who had just entered the sixth form at Oundle School. These letters provide rare glimpses of life in France but little of the daily horrors encountered in the trenches. Always beginning “My dear old Ted” and signed off “Your loving brother, Thomas L Warner”, Tom mostly showed concern about his younger brother’s health and achievements at school, along with keen interest in how Ted was managing the loan of Tom’s motorcycle. There was talk of occasional rugger matches in France played when conditions and time allowed: but mostly he referred to long hours spent working – this increased significantly when his majority was confirmed in late February 1917. Other Oundelians were mentioned as they passed through Tom’s theatre of war; and great anxiety was expressed about his friend, John Abbott, who was wounded but returning to the Front.

In April 1917, Tom was leading his men in a number of attacks on the Hindenburg Line, to which the German army had withdrawn and held in strength. For a second time Tom was awarded a Mentioned in Despatches (MID). During another attack in May he was so badly wounded that he was sent back to England, where he received treatment for what he told Ted was “an open wound in my back”, at the Regimental base in Leicester. This was convenient because by now the Warner family was living at Willowdene, London Road, Leicester. Tom’s gracious humility is epitomised in a letter to Ted referring to being Gazetted for another MID, “I have not the faintest idea what it’s for”. He continued to understate his true condition because he remained in England, with a back wound not healing, until late July when he finally persuaded a London Medical Board to declare him ‘fit for General Duties’. As one ever ready for “a little rugger if the opportunity arises” he took with him a rugby ball from home.

In early September 1917, he returned to command ‘C’ Company as a Major, just as the Third Battle of Ypres was underway. More commonly known as Passchendale, the Leicestershire Brigade manned the front line trenches at a place called Polygon Wood: a wood in name only as relentless artillery fire left only a seascape of mud and the occasional tree stump. To put this into some kind of perspective, the Brigade area of operations was about the size of Warners’ recently planted wood near Thrussington: an unintentional memorial to WW1 appeared in the summer of 2014 when a field of poppies unexpectedly appeared as a symbol of remembrance.

Tom’s letters began to reveal the horrendous conditions they now experienced: “It’s not normal but consolidated hell up here and I shall be glad to go to more human and healthy parts”. His desire was not fulfilled for in reality Tom was now leading his company into some of the fiercest fighting of the war. He wrote to his brother: “My dear old Ted, I’ve just come safely through a most hellish ten days”: not dwelling on his own misfortune, he then wished his brother well in a forthcoming school rugger match. His weariness of the war was once more clearly demonstrated by his words, “I wish I were going to play [a game of rugger] or have my school days again”. However, true to his kind, considerate and humble nature, he showed concern for his friend John Abbott, who badly wounded “has gone back to hospital in Leicester and will never come back to us again”. By 4th October the Brigade had been so severely reduced in numbers that the 8th and 9th Battalions were amalgamated for a few weeks. When replacement troops arrived Tom was put in command of the re-formed 8th Battalion until a new colonel took up the post at the end of the month.

In one of his last letters, he supported Ted’s wish to become a farmer – Ted was to fulfil his brother’s hopes: when undertaking farming experience at The Ems, Hoby, he fell in love with Winifred, one of the five daughters of Edwin and Alice James (i.e. Sue Warner’s grandparents) and became a farmer. Tom’s physical and mental condition, after almost continuous exposure to the violent horrors of trench warfare, was again evident from his words to Ted: “If I come through the war I shall help you to be a farmer, as I shall be a broken down old crock”. He was 23 years old.

Tom’s spirits were sinking as October progressed and the mud of Passchendale thickened. He reported that there were no more impromptu games of rugger in a place which was “exceedingly cold and unfavourable for living…a place where lights and fires are out of the question”. On 24 October, with typical understatement, he wrote to Ted: “I think you might like to know that I’ve got the DSO. It’s my first bit of ribbon – [he would have had to wait for the WW1 campaign medal before affixing the three oak leaves symbolising his MIDs] – I don’t know what it’s for and I’m quite thankful to be alive without getting anything else”. A few weeks later he explained further: “Someday it may be published in the Gazette what I got my bit of ribbon for [the DSO], but it was for the fighting up North [the Somme September 1916] – a souvenir of umpteen journeys through Hell”.

The Russian revolution interrupted any possibility of leave, and the Brigade returned to the front line. During a period spent in the reserve area around Tincourt, experiencing appalling weather and administrative chaos, Tom wrote his final letter on 14th December 1917. In it he mentioned he had just recovered from the flu and was now “quite alright again”. He asked his brother to send him the Oundle School Roll of Honour, which unbeknownst to him he was only days away from joining. Ever optimistic and enthusiastic for those he cared for and loved, he signed off his last letter with: “Hope you will have a very good holidays. Best love. Your loving brother. Thomas L Warner”.

On 15th December 1917 Tom was admitted to the 55th Casualty Clearing Station at Tincourt suffering from stomach pains. Just recovered from a bout of flu, weakened by dysentery, wearied by the heavy responsibility of leadership and two years in the trenches, Tom did not recover from emergency surgery for appendicitis and died on 27th December 1917 with his devoted servant Private B Hewitt at his side. A young man of great religious faith, with two wound stripes, 3 MIDs, a DSO, and a proven leader of men, died just two weeks short of his 24th birthday: in his own words “a broken down old crock”. Had Tom lived a fortnight longer he would have taken up a new posting and returned to England for a three month long staff course and promotion to Lt. Colonel.

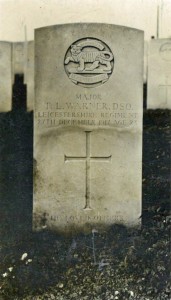

Tom was buried at Tincourt New British Cemetery in Plot 4, Row C, Grave #: 14. The inscription sums up perfectly the high esteem in which this young man came to be held by his family, superiors, peers and the men he commanded: it simply reads “He Loved Others”; the words were chosen by his Mother, Ida.

Many tributes were paid to Tom Warner in reflection of the ultimate sacrifice he made. Although a proven warrior it was generally agreed there never breathed a gentler soul. In a beautiful letter written in January 1918 to Ida by Tom’s servant and batman, Private B Hewitt, we realise and understand how much this gentle, warrior was loved, admired, and regarded by his men as “the bravest of the brave, fearless of danger, yet cool and resourceful, he combined good leadership with a kindliness and understanding of his fellow men”. Hewitt continued, “He was a man that seemed to us to be alone in his beautiful character insomuch as he lived the life of a Christian amidst surroundings that make it a terrible difficulty.”

Tom’s Mother, a widow since 1904 had lost her eldest son: then tragically her only daughter, Rachel, died just two months later. Ida devoted the rest of her long life – she died aged 86 in 1952 – to her son Ted, and to public service as an elected member of Leicester City Council.

No doubt Tom inherited his Mother’s ‘considerable strength of character’; something we can be sure helped him, throughout his very short life, to become the noble, gentle, considerate leader of men this country thankfully produced in abundance during The Great War.

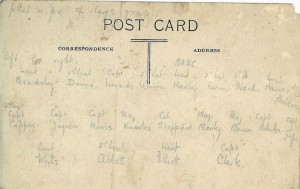

| The original exhibition display: Thomas Lovell Warner |